Masterplanning Development, Modernist Architecture, Urbanist Design

Modernism Architecture Urbanism: Future Masterplanning

Conference Paper by Professor Alan Dunlop – 15 Aug 2012

17 Oct 2012

Modernism in Architecture and Urbanism

ACADEMIC CONFERENCE

Xi’an Jiao tong-Liverpool University, Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, PR China 215123

18 + 19 Oct 2012

Masterplanning the Future – Modernism in Architecture and Urbanism

China, India and the West

BIG Lessons from a Small Place

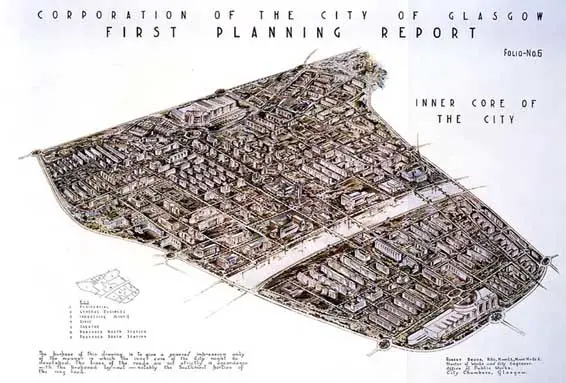

City of Glasgow 2012 (no larger images in this article):

image from Alan Dunlop

“Devastation was, however, proposed by Glasgow itself. The Bruce Plan of 1945 by the City Engineer reflected the utopian arrogance of the time by proposing the phased replacement of every single building in the city centre, which was to be surrounded by a box of new highways. Two decades later, the urban motorways that carved up the fabric of the city were on the lines drawn by Robert Bruce, but otherwise his Plan was mercifully forgotten.” The Glasgow Story …………

Abstract

The most vibrant, social and pleasurable cities have not been master-planned but instead have grown over time. Good planning is important but masterplans must not be prescriptive and must remain flexible to accommodate social and economic change.

Maintaining links with history and cultural identity is fundamental to successful master planning and retaining a sense of place is critical to good urban design. Cultural, Social and Physical change cannot be forced. A thorough understanding of social, material, historical and topographical context is crucial for the architect and urban designer.

Keywords

context; history; masterplanning; identity; sense of place

Introduction

image from Alan Dunlop

All Cities morph as populations change in line with industry, social and employment demands. Historically, few of the great cities of the world have been actively master-planned with most growing over time in an organic response to the environment and social and economic forces. Some embrace this change and manage to sustain improvements and provide environments in which to live and work, whilst others ossify and die.

Using Glasgow, my home city, as a model, I consider how transition from a city in industrial decline to a modern, prosperous place can be managed and examine the role of the master plan, urban planning and architecture in that process. I argue that for a city to thrive its politicians, people, planners and architects must all take a long-term view and steadfastly resist short term thinking.

Glasgow is a small city by Chinese standards, with a population of some 600,000 people. It is predominantly a Victorian City and was built on a highly navigable river, the Clyde. For many years it was considered to be the “greatest ship building city in the world” and between 1845 and the end of the Second World War, its yards built 25,000 major sea going vessels.

Shipbuilding on the Clyde was fundamental to the identity of the city and its people and brought wealth and prestige through trade with the USA and the British Empire. Today, there are only 3 small shipyards left which are entirely reliant on government contracts and the scars from the lack of investment and appropriate planning are visible everywhere in the city and its environs.

History and Context

Glasgow Shipyards 1945:

image from Alan Dunlop

Glasgow is over two thousand years old. It was originally a fishing village on a crossing point on the Clyde and in the sixth century, St. Mungo, a Christian missionary and the city’s patron saint, established Glaschu as a centre of Christian teaching. The city’s cathedral rose in the 12th century and the university, the fourth oldest in the UK, was established in 1451.

After the Act of Union with England in 1707, Glasgow flourished and become known as the “Second City of the Empire”. It was ideally located on the west coast of the new United Kingdom and it built the ships needed to expand an Empire and to establish trading colonies on the east coast of America and in the Caribbean.

The city has changed greatly over time, from the haphazard growth of the medieval city, to the creation of the Georgian City and, as trading increased and the city prospered, the setting out of the Victorian Grid. In an effort to combat the decline of its major industry, modern Glasgow has chosen to promote various grand regeneration initiatives; including the establishment of an International Financial Services District and the commissioning of the “starchitect” for prestige capital projects.

I suggest that even though the scale of Glasgow is much smaller than many Chinese cities, there are important lessons to be drawn from its decline and attempted regeneration. Political moves to re-position the city internationally in today’s fast moving and highly competitive global economy by radical reform of its physical infrastructure and space can provide a test bed for others.

Glasgow’s experience is similar to other cities, including many here in China, that face decisions about competing in a modern market whilst trying to retain both culture and identity. It is the impact of Glasgow’s political, planning and architectural decisions that forms the body of this discussion.

Master-planning Glasgow’s Future

image from Alan Dunlop

Glasgow is infamous for its past planning failures. In 1945, the city commissioned “The Bruce Plan”, a prescriptive master plan which proposed to sweep away most of the Victorian, Georgian and Medieval fabric of the city and to replace it with a “Brave New World” of modernism. The plan included the wholesale demolition of all historic structures and the grid in favour of sweeping vistas, wide roads and motorways.

The notion was to bypass the centre of the city and required the movement of hundreds of thousands of people to new satellite housing outwith the city on “green sites”. Had the plan had been fully implemented, Glasgow would now resemble East Berlin or Bucharest and only the Cathedral would have remained. In some places where the 1945 plan was partly fulfilled, the resemblance is so strong that many Hollywood films use the city to represent the “Cold War” Eastern Europe.

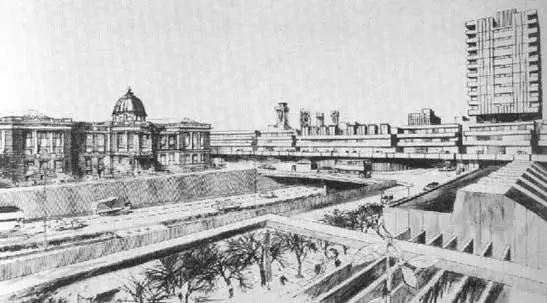

The proposals were however, never fully executed although much of the road and motorway routes were built, including the M8 motorway, the Kingston Bridge and Clydeside Expressway which cut through much of the Victorian centre and brought about the whole-scale destruction of established neighbourhoods, isolating business and commercial quarters from previously linked social districts.

Many fine buildings of historic and architectural value were destroyed or left marooned with their environmental context decayed. Later, Glasgow’s traditional tenement housing stock was also considered substandard and much was demolished as whole communities were displaced.

The “improvements” were in homage to the motor car as the great social freedom and denied the requirement for social interaction and creating a sense of place that makes any city great. In particular, the city was spoiled when pedestrian access to the river was cut off. Central planning and “quick fix” residential projects were completed that moved families and communities out of the traditional housing and into peripheral new housing estates, with neither cohesion, identity nor industry.

The result was the atomisation of many communities and the destruction of large sections of historic city fabric. Many of the new estates were of poor quality and have themselves since been razed to the ground. The social legacy has been to de-populate large tracts of the inner city, leaving patchwork sections of community isolated and to instil in much of the population a deep distrust of urban planning and a distaste for modern architecture.

These failed plans coupled with the wholesale destruction of historic buildings also delivered a general rise in interest in conservation, in an attempt to protect older buildings, regardless of their quality or utility and this has lead to a stock of empty and often decaying Victorian buildings in the city centre.

Planning applications for new projects in the West End of the city, perhaps its most notable concentration of complete and authentic historic buildings can attract thousands of recommendations for rejection from local people. In the city centre, it is now nigh on impossible to put forward any building proposal that alters the Victorian grid or necessitates the demolition of an old building or facade.

Today architects work with the city’s historic grain. Although Glasgow is considered a centre of contemporary architecture this masks a deep resistance to any change to its historic fabric. The errors wrought by the legacy of previous master-planners coupled with the social displacement have brought strong conservative views to the fore and Glasgow continues to struggle with the impacts of decisions first envisaged in 1945. As a result there is sometimes a lack of coherence in how the city responds to changes in commercial infrastructure demands and altered social needs in housing, transport, education and leisure.

To use a medical analogy, the city fathers master planning prescription did not improve the health of the city but served only to make the patient weaker and less able to deal with the newer travails that it faced. Today’s physical planning and regeneration initiatives have little real impact on the city’s development. So what is the alternative?

The “Bilbao Effect”

Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum project in Bilbao persuaded the civic leaders of many provincial cities that major architectural projects can bring substantial economic benefit through tourism, jobs and increased profile. It is estimated that the economic value added by the Guggenheim Museum was €168 million and that the project created nearly 5,000 new jobs.

A recent survey reported that over 80% of visitors to Bilbao in the last ten years came exclusively to see the museum. Since its creation, there have been many attempts to replicate the “Bilbao Effect” but very few new museums or galleries outside major cities have succeeded in making the same impact.

Cities like Glasgow compete with other regional and European centres for international business and so seek global recognition through branding, so it too needed a catalyst.

In Scotland, city authorities continue to strive to recreate the Bilbao Effect by commissioning high-profile capital projects using international architects, with no link to the country in some cases or little obvious understanding of context or its history. Glasgow has a new Riverside Museum by Zaha Hadid, Dundee is building a new Victoria and Albert Museum by the Japanese architect Kengo Kuma and Diller Scoffidio and Renfro has designed Aberdeen’s Union Terrace Gardens proposal.

All three projects were subject to an international architectural competition, which although not excluding regional architects who perhaps might understand the local challenges and context better were not considered to have necessary international standing to secure the projects.

This commissioning of high-profile architects suggests a general lack of confidence in local talent and confirms the need for external validation from local politicians and funders, which is in some ways understandable. All organisations need to raise substantial monies for a major projects and the risk of failure to do so can sometimes be mitigated by a high-profile name. What it also disappointingly confirms is a lack of belief in historical referencing and architectural ambition as the resulting projects tend to be iconic, ubiquitous and “bolted on”, rather than a sensitive response to a particular place or local need.

Architectural Fixes

Glasgow, as I have described, rose from the river and its heritage is outgoing, building vessels and international trading. Regrettably the river, which was once the lifeblood of the city, has been allowed to degenerate with dredging to keep it navigable stopped, fewer and fewer ships are being built, and little social activity. This is another indictment of poor long-term planning and a lack of vision from civic leaders.

More recent piecemeal ”design and build” solutions and opportunistic development have been disappointing and are not the answer either, for such approaches bring with them competing interests, divisive attitudes and provide little opportunity for commissioning coherent public space. There really has to be a long-term and over arching plan that sets both an end game as well as ensuring high standards for on- going design and building quality.

There are projects which have attempted to revive civic and cultural interest and which could stimulate activity around them but few have achieved the high standards promised at their inception. Norman Foster is currently building another extension to the Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre (SECC) on the riverfront. Like the “Armadillo”, his previous project for the SECC, it is an “iconic” structure.

It stands alone surrounded by car parking and takes no reference or joy from its riverside setting. Little is known about the process leading to the commissioning of Foster or the development of the design for the building and public debate was not encouraged. Like the Riverside Museum by Hadid, it was thought that a building by the likes of Foster would be enough to focus world attention on the city. Such a tactic may have worked but not without a first-class design.

The Hosting of International Events

In 2014, Glasgow will host the Commonwealth Games, the world’s third largest multi sport event and which involves athletes from Britain’s commonwealth nations. The city authorities believe that the games will provide an international showcase and bring substantial economic and social benefit, whilst also regenerating moribund areas of the city.

The games will cost £540 million and are part funded by Glasgow City Council and the Scottish Government. It is claimed that tourism will increase by 4% and that the economy in Glasgow will be boosted by £30m and that 1,000 new jobs will be created. Although it is indisputable that these events increase the profile of a city, it is arguable how much sustainable “economic and social legacy” they bring. These events are an act of faith.

Suzhou

Aerial view of Suzhou Industrial Park, Central Business District, 2006, Suzhou, China:

image Courtesy of Suzhou Industrial Park Administrative Committee

As you are all aware, China is the world’s second largest economy with a GDP of 7.6 % last year, which is remarkable by western standards. The country maintains its commitment to modernity and has multiple urban design and massive infra structure projects going on.

Here in Suzhou, one of China’s most ancient cities, a new university town is being built which will be the hub for twenty five of the world’s top universities. There is much that Suzhou and other Chinese cities can learn from Glasgow’s planning experience over the last fifty years. China is facing its own architectural revolution, battling between conservation and modernity; it seems unaffected by issues of identity, evolution and built heritage.

The Suzhou Industrial Park (SIP) is a joint cooperation between the Chinese and Singapore governments. It has been planned on a Singapore city model, with wide boulevards for the car, a grid and wide open spaces that are marked with stand alone architectural icons, some of which are admittedly very good. The quality of the public realm and landscaping is beautifully crafted and finished but is not recognisably Chinese.

The comparison with Suzhou old town is marked. The old town is authentically Chinese; not a pastiche but a city built up over time. The city is bustling and business is going on at street level. There are working waterways and pedestrian areas, shops and cafes and UNESCO World Heritage gardens.

There is an architectural language evident in the white walls, black eaves and roofs. People live and work in the same area and buildings are predominantly three and four storeys and of a human scale. Yet, although all the clues are there, nothing of the place seems to have influenced the architecture and urban design of SIP. Instead older buildings have been systematically removed and a new modern environment created. An environment which is pleasant, clean and air conditioned but charmless and alien.

In fact, to the eye of the newcomer the new campus feels like it could be anywhere and at this point lacks character. The environment has been created to attract business and is succeeding. The campus is over 300 km2 with a population currently of around 1m which will rise to 1.5 million in five years.

You would not know that Suzhou is forty minutes by bullet train from Shanghai, the most “European” of Chinese cities and currently the biggest container port in the world with aspirations to be the world’s leading cruise ship destination.

However, you cannot but compare the new environment created at SIP with Suzhou city and the authenticity of the old town. SIP lacks any particular sense of place and identity, although this may come in time.

Urban development in China is progressing at a remarkable pace. The last twenty years have seen extraordinary changes to the country’s physical and social landscape and infrastructure that are astonishing. Yet, like Glasgow, it may come to regret many of the quick fix changes to its cities and towns if it continues to ignore its built tradition, architectural history and precedent.

The country has many outstanding regional architects, now gaining an international reputation outside China and who have been trained in the country’s most prestigious schools. Their architectural expertise is now needed to plan a positive way forward for the county’s new cities. Plans which should take much more account of China’s three thousand year built history, to create authentic city environments which are pleasurable and have a real sense of place whilst also addressing the country’s global and economic ambition.

Professor Alan Dunlop FRIAS FRSA

Masterplanning the Future – Modernism in Architecture and Urbanism images / information from Professor Alan Dunlop

Comments on the Modernism in Architecture and Urbanism article are welcome.

Location: Suzhou, China

International Architectural Designs

Architectural Competitions : links

Architecture Articles

Recent articles for e-architect

Architectural Articles on e-architect : Selection

Contextual Architecture : article by Roland Wahlroos-Ritter

Cultural and Contextual Identity : article by Nigel Henbury

Resisting Boredom : article by Joyce Hwang

Comments / photos for the Future Masterplanning – Modernism in Architecture and Urbanism page welcome